Book Chapter: Resonances between heuristic inquiry and Persian illuminative thinking

This is chapter 3 of the book "Heuristic Enquires" edited by Professor Welby Ings and Professor Keith Tudor

Written by: Hossein Najafi

Introduction

This chapter proposes a dynamic interplay between heuristic inquiry and Illuminative thinking, by developing and examining a unique blend of Western and Persian epistemologies. Drawing from a rich corpus of Persian literature and philosophy, particularly the works of philosopher Shahab al- Din Suhrawardi and the poet Farid al-Din Attar, I demonstrate how the ancient philosophy of illuminationism might enrich contemporary heuristic approaches to inquiry, and in doing so, argue for a culturally dexterous research paradigm which is systematic, shaped by praxis, and capable of engaging with a researcher’s intuitive insights. In this chapter I include spe- cific Persian terms and provide approximate translations for some key terms as a way of drawing a closer connection between two distinctive realms of thinking.

Research

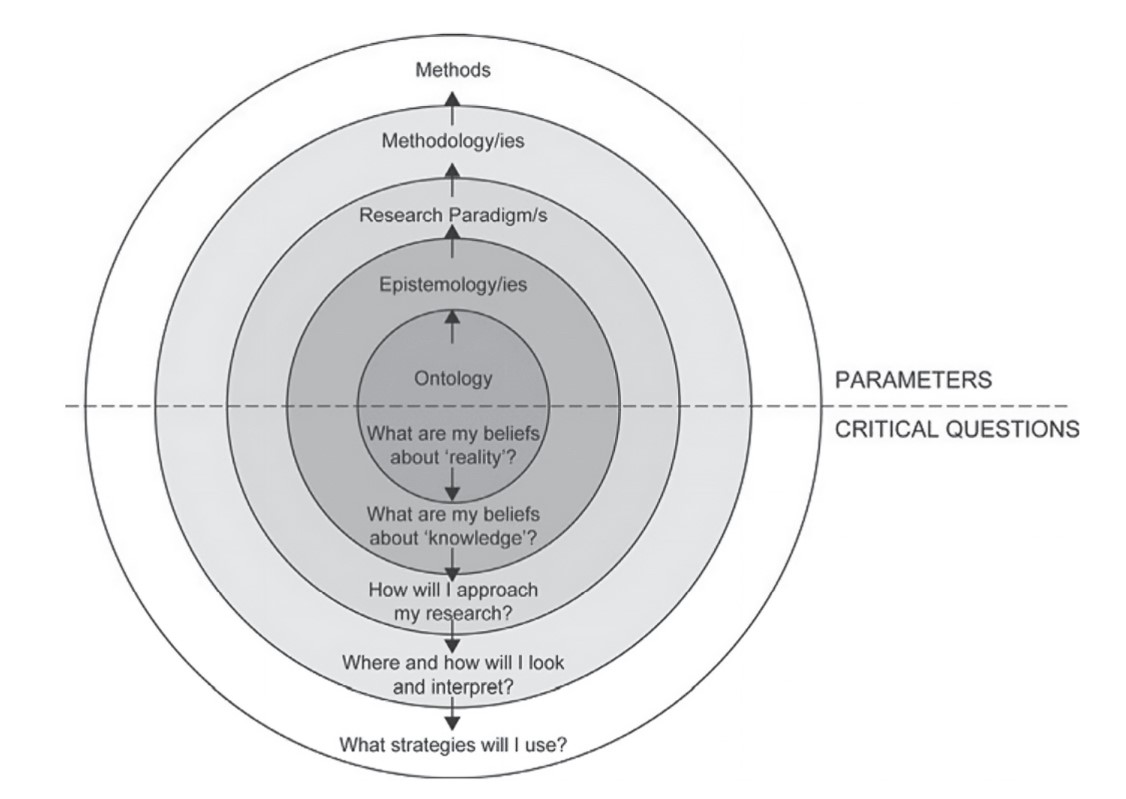

Mockler (2011) and Wagner et al. (2012) note that a research paradigm ema- nates from the way a researcher sees the world and that the nature of reality and ways of knowing lie at the heart of research design. They suggest that once a research paradigm is established, then the researcher considers how to study the world through a systematic inquiry by asking certain questions that shape the project’s methodology, and then methods that are employed to address specific parts of the study. Mockler (2011) argues that the research’s paradigm, methodology, and methods are all linked to the researcher’s ontol- ogy and epistemology (Figure 3.1).

FIGURE 3.1 Relationships within a research design. Source: Reproduced with permission from (Mockler, 2011, p. 160).

Research paradigm

A paradigm is‘a body of beliefs and values, laws and practices that govern a community of practitioners’ (Carroll, 1997, p. 171). Paradigmatically, many of my personal research projects and the master’s and doctoral theses I super- vise may be understood as artistic inquiries (Klein, 2010) which employ forms of practice-led study. As an Iranian researcher my orientation is influ- enced by Persian literature and philosophy and as such, what underpins my understandings is partly shaped by اشراق (Ishraq), i.e., illuminationism and by Western approaches to research design. This gives rise to forms of inquiry that we might describe as an illuminationist, artistic, and practice-led.

Artistic research

In 2010, Julian Klein discussed a research orientation he called artistic research. He proposed that if we consider art as a mode of perception, then we can think of artistic research as the mode of a process. In such an orientation, reflection on research occurs inside the artistic experience itself (Klein, 2010). Most challenges, questions, and problems in artistic inquiries are shaped through the creative endeavours of the practitioner who engages practical methods that emerge from internal experiences (Gray, 1996). Practice may engage a multitude of methods (Haseman, 2006) that are exercised in a pro- cess of intervention, creation, and conversion, that may either produce knowledge or heighten understanding (Scrivener, 2000). Barrett and Bolt (2007) suggest that it is through a process of elucidation and clarification that new knowledge emerges, and this moves beyond the artist beyond solipsistic, reflective practice.

Practice-led research

I use the term practice-led research to describe an inquiry that is led through practice. In other words, the researcher employs practice as both an agent of questioning and discovery. In practice-led artistic research, both Hamilton (2011) and Ings (2015) suggest that a dynamic exists between theory and practice, such that as the researcher shapes their work, they in turn are shaped by questioning and discovery. Such research calls theory to itself and theory is questioned and shaped within the researcher’s practice. I would argue that, as a consequence, theory merges with the self through an embodiment that invigorates and revitalises the inner voice. This is because practice-led artistic research is, as Gray puts it, ‘simultaneously generative and reflective’ (1996, p. 10). The relationship between what is interior and what is generated through practice may result in elevating both the self (the artist) and the body of knowledge (Chen, 2018; Ings, 2018; Pouwhare, 2020). This might be lik- ened to the Chinese concept of Zhe Jiang where tenacity leads to reverence, reverence leads to expertise, expertise leads to vision, and vision leads to the researcher not only increasing artistic ability but also becoming a better per- son (Chen, 2018).

Illuminationism

Over a thousand years ago, Suhrawardi’s الاشراق حکمت (The Philosophy of Illumination) (1186/2000) shaped Persian literature and architecture by blend- ing Hermetic, Pythagorean, Zoroastrian, Islamic, Platonic, and Neoplatonic symbolism (Nasr, 1964). Illuminationism emphasises the primacy of expe- rience and intuition (Ziai, 1990), knowledge by presence, and the impor- tance of imagination and innovation (Marcotte, 2019). During the same era, Persian poets like Rumi and Attar exemplified and heightened the tenets of illuminationism (Aminrazavi & Nasr, 2013). By retrieving a large corpus of ancient texts, Suhrawardi (1186/2000) was the first scholar to realise that the sources of Persian and Greek wisdom might be related. He sought to reu- nite Greek and Persian wisdom lost after Aristotle, recognised connections between the two wisdom traditions, and advocated for a universal and per- ennial wisdom beyond Aristotle’s rationalistic approach. His work shaped a new way of conceiving intellectualisation and practice in the Iranian-Islamic world, and his thinking remains delicately manifested in much Iranian- Islamic art and architecture (Rahbarnia & Rouzbahani, 2014). Ziai (1990) and Aminrazavi and Nasr (2013) all suggest that Suhrawardi’s legacy still per- meates Iranian cultural and academic understanding. Suhrawardi’s philoso- phy of Illumination uses the non-corporal, allegorical ontology of light as an intellectual substrate. His thinking took diverse forms including symbolic and mystical narratives that considered the journey of a soul across the cosmos to, as Nasr notes, a ‘state of deliverance and illumination’ (1964, p. 59).

Significantly, the philosophy of Illumination considers practice as a mode of intellectual engagement (Ziai, 1990) and places emphasis on intuition and knowledge by presence. It also positions imagination and innovation at the centre of its ontology (Marcotte, 2019). Although Suhrawardi’s The Philosophy of Illumination is considered a seminal text on illuminationism, Dabbagh (2009) notes that Suhrawardi’s thinking permeated the work of many intellectuals, artists, and poets of the period. Even Ibn Sina, the most prominent Peripatetic (Aristotelian) philosopher in the Islamic world (known as Avicenna in the West) wrote three treatises on illuminationism towards the end of his life.

In considering the concept of illuminationism in this chapter, I have drawn on the thinking of two philosophers, Ibn Sina and Suhrawardi, and one poet, Attar of Nishapur, a prominent Persian poet and mystic. According to Zwanzig (2009), as an illuminationist, Attar offers an important perspective on self- discovery through his work The Conference of The Birds (Attar, 1984). Attar’s approach as a practitioner, his storytelling skills, and his elaboration of the gradual progression of internal exploration, may be seen as resonating with heuristic approaches to inquiry as a journey that is undertaken without a pre- set, formulaic template.

Knowing through praxis

Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi (1236–1311), one of the earliest commentators of Suhrawardi, suggests that illuminationism is the intuitive revelation of intel- lectual lights and their overflow on the self (Berenjkar, 2019). According to Aminrazavi and Nasr, ‘both metaphysically and historically, illuminationist (اشراقی) philosophy refers to an ancient pre-discursive mode of thought which is intuitive (ذوقی) rather than discursive (بحثی) and seeks to reach illumination by asceticism and purification’ (2013, p. 130). Epistemology is at the core of the philosophy of illumination and its definition of knowledge is what dif- ferentiates it from the canonical peripatetic tradition; as Suhrawardi notes, knowledge is the ‘presence and the emergence of the things to the intellectual self’ (quoted in Beheshti, 2015, p. 55). Yazdi suggests that this ‘knowledge by presence’ (1992, p. 1) is achieved in the process of self-awareness and the feeling of existential states.

Ziai suggests that art and literature become the metalanguage of illumina- tion as the vehicle to achieve knowledge, because in these realms knowledge passes through ‘the experienced and the imagined’ (1990, p. 216). Ziai also suggests that poetic language and the use of metaphors, allegory, symbolism, and references to myths and legends can function as a way to not only con- template and internalise the knowledge of the things, but also to reach beyond philosophical discourse and reach out to a wider audience.

At the beginning of his book, Suhrawardi states that:

"Although before the composition of this book I composed several treatises on Aristotelian philosophy, this book differs from them and has a method peculiar to itself. All of its material has not been assembled by thought and reasoning; rather, intellectual intuition, contemplation and ascetic practices have played a large role in it. Since our sayings have not come by means of rational demonstration but by inner vision and contemplation, they cannot be destroyed by the doubts and temptations of the sceptics. Whoever is a traveller on the road to Truth is my companion and aid on this path." (Suhrawardi (1186/2000, p. 10))

Suhrawardi was a prolific scholar, and his early writings, which use a classical lexicon and literature, are mostly commentaries on Avicenna’s peripatetic phi- losophy. During his long travels through Persia, India, Anatolia, and Syria he met many poets, mystic sages, Gnostics, and Sufis and thereby became acquainted with a large number of ancient texts. As a consequence of these interactions, he gradually elevated his philosophy to illuminationism into which, and especially in his later writings, he integrated a significant range of Hermetic, Pythagorean, Zoroastrian, Islamic, Mystic, Platonic, and Neoplatonic symbolism (Nasr, 1964). As a consequence, there was a shift in his style of writing as he began incorporating poetry and narrative stories into his philo- sophical writing. Although at this time, Arabic was the official intellectual and scientific language of the Islamic Golden Age, Suhrawardi wrote most of his treatises in Persian, and the titles of his treatises reflect a creative and poetic sensibility: Treatise on the State of Childhood, Treatise on the Nocturnal Journey, The Red Intellect, The Chant of the Wing of Gabriel, The Occidental Exile, The Language of Termites, and The Song of the Simurgh (Walbridge, 2011).

Even though he prioritised the primacy of experience in the Philosophy of Illumination, Suhrawardi does not dismiss reason and rational thinking (Ziai, 1990). While acknowledging and explaining intuitively attained knowledge, Suhrawardi still proposed using rational reasoning and the classical mecha- nisms of logic albeit in a different order. In other words, the main difference between peripatetic philosophers and Suhrawardi lies in where to begin an inquiry: either one moves from discursive knowledge towards intuition (like Avicenna), or one begins from experience and intuition and then progresses towards the rational and the reasoned (as Suhrawardi suggests).

This is why many scholars consider illuminationism as an example of the fusion of Platonian intuitionism and Aristotelian rationalism (Corbin, 1964; Marcotte, 2019; Nasr, 1964; Walbridge, 2001; Ziai, 1990). Contrary to the peripatetic philosophers, Suhrawardi believes in the primacy of essence over existence. He also rejects the peripatetic notion that we are never able to know the essence of things (Beheshti, 2016). He maintains that the sole act of constructing the definition of a thing does not reveal its essence and it is a tautology (.الالفاظ تبدیل). Because of this, Suhrawardi proposes the idea of illuminationist vision (اشراقی مشاهده). Here, the researcher opens their inner eye through an act or a journey that begins with a quest and demands practice and engagement. The object of study becomes luminous and excited to the state of illumination and then becomes knowable to them through experience and imagination (Ziai, 1990). In other words, vision is ‘seeing through praxis’ (Ziai, 1990, p. 218). Henry Corbin, the first translator of Suhrawardi into a Latin language, calls this realm mundus imaginalis (Corbin, 1964).

Suhrawardi’s world of lights and illumination should not be read as the Platonic theory of forms and ideas (although he has borrowed some compo- nents from Plato). The difference lies in the plasticity of Suhrawardi’s world of lights. Suhrawardi maintains that creators and artists, through rigorous prac- tice, attain illumination and reach a condition that he calls the state of Be (کون مقام). This could be considered close to Sela-Smith’s (2002) concept of inward reach. Suhrawardi suggests that, by their luminosity, they can shape the celestial forms and bring them to the terrestrial domain where they turn into works of art or abstracted concepts (Shafi & Bolkhari, 2012). Accordingly, for Suhrawardi, there is a dynamic dialogue between the realm of imagina- tion (mundus imaginalis) and the realm of earthly self.

The foundations of illuminationism were outlined in the first chapters of Suhrawardi’s book, The Philosophy of Illumination. However, reading his writings is not an easy task for a researcher. His narrative stories can feel like psychedelic reflections of a mystic dreamer, full of references to myths and symbols. Compared to the scholastic structured writings of peripatetic philos- ophers such as Avicenna, Suhrawardi’s works may seem chaotic, tangled, enigmatic, and scattered. One reason may be because he had no time to organise his writings because following an accusation of heresy by Islamic jurists of Hallab he was executed at the age of 37, and he wrote his most important book, The Philosophy of Illumination, in about a month while in prison awaiting his execution.

Heuristic enquiry

In artistic research, heuristic inquiry can be framed as a form of discovery achieved and elevated through practical experience. Through the process of the practice, the researcher works without a predefined formula, using astute observation and questioning to explore and develop potentials within the work incrementally. Accordingly, the direction of the inquiry may change or be adjusted, and new questions may arise (Ings, 2011; Kleining & Witt, 2000; Moustakas, 1990). The protean nature of creative inquiry demands an adaptive strategy because not only the process but also the questions and problems that arise need to be reflectively adjusted (Ings, 2011). Heuristic inquiry character- istically employs both explicit and tacit knowledge and draws heavily on self- search, phenomenologically reincarnated reminiscences, and internalised wisdom that can result in new approaches (Douglass & Moustakas, 1985). In a heuristic inquiry the dynamic sphere needs to be iteratively updated to portray the active evolving quest of the researcher, and so the approach requires a concatenation of integrated re-adjustments and re-definitions (Scrivener, 2000). Moustakas (1990) suggests that because heuristic research is concerned with interrelated and integrated elements it restores derived knowledge as a form of creative discovery that accompanies intuition and tacit knowing. The research process begins within the practitioner and their interior dialogue. Accordingly, one cannot expect the predictability factors and casual relations that we encounter in empirical inquiries. Thus, Moustakas (2001) notes that heuristic inquiry is illuminated through careful descriptions, illustrations, metaphors, poetry, dialogue, and other creative renderings rather than by measurements, ratings, or scores.

Illuminative heuristic inquiry

Having discussed the nature of illuminationist thinking, it is useful to consider how it might impact on a research methodology designed for artistic inquiry. Chilisa and Kawulich suggest that ‘methodology is where assumptions about the nature of reality and knowledge, values, theory and practice on a given topic come together’ (2012, p. 51). In my research I employ heuristic inquiry, but I look into it through the lens of Suhrawardi’s Persian illuminationism. In exercising this connection between Western and Persian methodological thinking, I draw upon the metaphors of another Persian illuminationist, the poet Attar of Nishapur, whose famous poem The Conference of the Birds describes the journey of the self through an allegorical narrative.

Seven concepts/processes of a heuristic inquiry

In his book Heuristic Research, Moustakas (1990) suggests that research begins with a question that requires illumination and notes seven concepts or processes that underpin the researcher’s pursuit of a deeper understanding of the phenomenon being explored, i.e., identifying with the focus of inquiry, self-dialogue, tacit knowing, intuition, indwelling, focusing, and the use of the internal frame of reference.

Identifying with the focus of inquiry

In this process Moustakas describes a state similar to Suhrawardi’s concept of the internal unification of the researcher with the question. Both scholars propose what Moustakas refers to as ‘immersion in active experience’ (1990, p. 2), which is achieved by delving freely into one’s self. In this sense, both suggest that through this process the inquiry becomes identifiable.

Self-dialogue

Self-dialogue involves researchers immersing themselves in the phenomenon. This approach necessitates openness, receptiveness, and attunement to all facets of their experience with the question under consideration. Self-dialogue integrates intellect, emotion, and spirit in a disciplined manner (Bronowski, 1965; Craig, 1978). It also elevates the importance of being open to one’s experiences, trusting in self-awareness, and maintaining an internal locus of evaluation throughout the research process (Rogers, 1969). This self-directed approach defies pre-imagined formulae but, rather, draws upon perceptual powers afforded by direct experience (Douglass & Moustakas, 1985).

Tacit knowing

Polanyi (1964, 1983) emphasises tacit knowledge as a foundational element of comprehension. He suggests that the tacit dimension permeates the research process, guiding the researcher into new directions and sources of meaning because he maintains, ‘We can know more than we can tell’ (Polanyi, 1983, p. 4). This concept suggests that there are things we under- stand intuitively and can apply or recognise, without being able to explicitly state or explain them.

Intuition

Intuition operates as a bridge between tacit, implicit knowledge, and a jour- ney towards explicit, definable knowledge. Intuitively, the researcher drives knowledge immediately and directly, crosscutting logical reasoning.

Indwelling

This process involves immersing and living within the depth of the inquiry so that the researcher is able to reflect on details. Moustakas describes this as ‘a painstaking, deliberate process. Patience and incremental understanding are the guidelines. Through indwelling the heuristic instigator finally turns the corner and moves toward the ultimate creative synthesis that portrays the essential qualities and meanings of an experience’ (1990, p. 10).

Focusing

This refers to a process where the researcher clears away disparate qualities to concentrate on core meanings that define an experience. Douglass and Moustakas suggest that this process is concerned with the ‘refinement of meaning and perception that registers as internal shifts and alterations of behaviour’ (1985, p. 51).

The internal frame of reference

The heuristic process is grounded in the researcher’s internal frame of refer- ence, which is vital for understanding the nature, meanings, and essences of any human experience. Rogers (1951) maintains that empathic understand- ing and open, trustworthy communication are crucial for comprehending another’s experience from this internal viewpoint.

Attar’s illuminationist journey of the self

Having considered Moustakas’ seven concepts or processes underpinning heuristic inquiry, I turn to the thinking of Attar of Nishapur (1145–1221), the prominent Persian poet and mystic whose works shaped the landscape of Persian literature during the 12th century. Attar pursued a form of illumination- ist self-discovery (Zwanzig, 2009). Although Attar lived at the same time as Suhrawardi, there is no historical record indicating that these thinkers met or maintained any form of correspondence (Mojtahedi, 2015), though Bahonar (2010) notes that the language, mythology, references, symbolism, and espe- cially the illuminationism in his works, particularly in Attar’s (1984) The Conference of The Birds, are akin to Suhrawardi’s.

In contrast to the philosophical approach of Suhrawardi, Attar approached illuminationism from the position of a practitioner, though like Suhrawardi, Attar believes that wisdom is ‘moving’ and the path to wisdom is not prede- termined but, instead, shaped by ‘going’ (Afshari-Mofrad et al., 2016). In a structured, poetically explained expedition, Attar elaborately documents the gradual progression of an internal exploration. Although Attar was not the first person to talk about processes of a mystic journey, he is one of the earliest to construct a framework and clarify a system through an allegorical narrative, providing examples to elucidate each process which, in effect, form stages of the mystic – and, by analogy, research – journey.

Attar offers similar ideas regarding phases in a journey to Moustakas (1990) regarding certain processes that underpin heuristic inquiry. For these reasons, I have come to adopt Attar’s concepts (over Suhrawardi’s) in shaping my Persian approach to heuristic inquiry. Although many intellectuals during the Islamic Golden Age wrote stories using bird metaphors, Bahonar (2010) suggests that Attar’s The Conference of the Birds is the finest example, both in terms of literature and conceptual cohesion.

Attar’s The Conference of the Birds begins with a question posed among the birds of the earth: ‘Who is our king?’ The Hoopoe, the wisest of all, informs them of Simurgh, a divine bird who is the source of all the life and diversity in the universe. He claims the magnificence of China, the splendour of Persia, and all varieties of beauty around the world exist because the Simurgh has flown over those lands on each of which one of her glorious feathers has fallen. Her nest, he says, is on the Tree of Knowledge located on Mount Qaf, the peak of the world.1 To reach Mount Qaf, the birds have to travel on an arduous journey through seven valleys. Most of them give up, return, or die. Eventually, out of thousands, only 30 birds2 arrive at the magnificent throne of the Simurgh… but she is not there. Towards the dawn, when the sun illumi- nates, these birds see their shadows on the throne, and they realise that each of them contributes to a composite that is Simurgh.

The seven valleys

In this section I discuss the seven valleys which comprise the seven processes of a mystic journey, selecting a few lines from Attar’s poem to illustrate the core meanings of each concept.

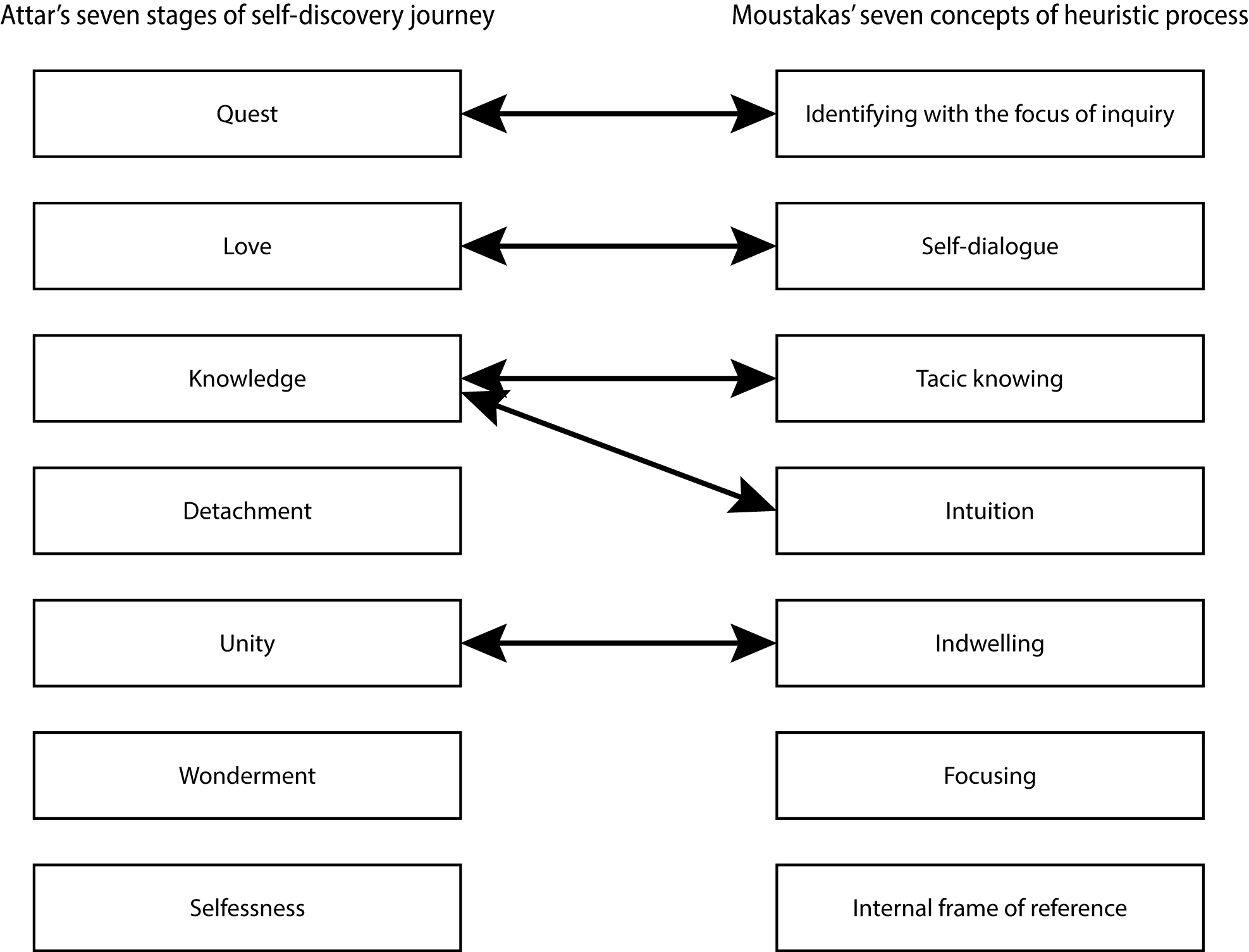

First, I compare Attar’s stages of the journey of self-discovery with certain concepts of heuristic inquiry as described by Moustakas (1990) (Figure 3.2). As may be seen, the first three stages and concepts as well as the fifth in Attar’s scheme have a surprising resonance with Moustakas’ heuristic concepts. The concept – and stage – of knowledge in Attar’s journey has qualities of both tacit knowing and intuition in Moustakas’ model. I found the detachment process in Attar’s story a pure Eastern gnostic perspective with no parallel in Moustakas’ model, though has some resonance with his concept of incuba- tion, which forms one of the phases of heuristic enquiry. I suggest that the last two processes of both models are vastly different (see p. x, below). I don’t find any resonance between Attar’s concepts of wonderment and selflessness and Moustakas’ concepts of heuristic inquiry, though there is some echo of self- lessness in Sela-Smith’s (2002) concept and encouragement of surrender.

FIGURE 3.2 Comparison of Attar’s stages – and concepts – of the journey of self with Moustakas’ concepts of heuristic inquiry.

The valley of quest

When the birds, motivated by Hoopoe’s speech, embark on their journey to find Simurgh, the first encounter that challenges them is the valley of quest. This may be aligned with the first process in Moustakas’ (1990) heuristic jour- ney which involves the researcher identifying – and, I suggest, unifying – with the subject of inquiry. Similarly, Attar urges the birds to free their hands and minds from all distractions and internalise their quest and let their longing heart be illuminated by the splendour of their passion. This concept in Attar’s journey is similar to that of Moustakas ‘identifying with the focus of inquiry’ (1990, p. 15).

ملک اینجا بایدت انداختن ملک اینجا بایدت در باختندر میان خونت باید آمدن وز همه بیرونت باید آمدنچون نماند هیچ معلومت به دست دل بباید پاک کرد از هرچ هست چون دل تو پاک گردد از صفاتتافتن گیرد ز حضرت نور ذات چون شود آن نور بر دل آشکار در دل تو یک طلب گردد هزار Renounce the world, your power and all you own, And in your heart’s blood journey on alone.When once your hands are empty, then your heart Must purify itself and move apart,From everything that is. When this is done,The divine light blazes brighter than the sun, Your heart is bathed in splendour and the quest Expands a thousandfold within your breast. (Attar et. al, 1984, p. 238)

The Valley of Love

The second encounter is the valley of love. For Attar, love here is more intro- spective and contemplative than physical attraction. In the valley of love, those birds who couldn’t connect with the love within quit the journey. It has the quality of Moustakas’ (1990) concept of self-dialogue. The state of self- exploratory love that Attar is talking about here ascends the lover to a state beyond morality, where good and evil seem the same. Moustakas (1990) refers to the fact that because the researcher has already identified with the subject of study both enter into an intense, internal dialogue where the ‘self’ engages in a questioning conversation with the subject of inquiry. In Attar’s valley of love, the wayfarer becomes attuned with their own presence and constituents. This concept can be interpreted as Moustakas’ ‘self-dialogue’ (1990, p. 16).

بعد ازین وادی عشق آید پدید غرق آتش شد کسی کانجا رسیدکس درین وادی به جز آتش مباد وانک آتش نیست عیشش خوش مبادلحظهای نه کافری داند نه دین ذرهای نه شک شناسد نه یقیننیک و بد در راه او یکسان بود خود چو عشق آمد نه این نه آن بودگر ز غیبت دیدهای بخشند راست اصل عشق اینجا ببینی کز کجاستگر ترا آن چشم غیبی باز شد با تو ذرات جهان هم راز شد ور به چشم عقل بگشایی نظرعشق را هرگز نبینی پا و سر Love’s valley is the next, and here desire Will plunge the pilgrim into seas of fire, Until his very being is enflamedAnd those whom fire rejects turn back ashamed. Who knows of neither faith nor blasphemy, Who has no time for doubt or certainty,To whom both good and evil are the same, And who is neither, but a living flame.If you could seek the unseen you would find Love’s home, which is not reason or the mind And see the world’s wild atoms, you would know That reason’s eyes will never glimpse one spark Of shining love to mitigate the dark.Love leads whoever starts along our Way(Attar et. al, 1984, p. 241)

The valley of knowledge

Attar describes this form of knowledge as intuitive, and one that enables a (re) searcher making a journey to realise their unique personal qualities. This is similar to Polanyi’s (1966) idea of tacit knowing, which Moustakas (1990) adopts, as well as the concept of ‘intuition’. In this phase of their quest each bird must come to an innate knowledge of its own road, i.e., a path that is different for each of them. These routes are very elastic and are shaped by each individual. No bird is able to comprehend or understand another bird’s trajectory.

هیچ کس نبود که او این جایگاه مختلف گردد ز بسیاری راههیچ ره دروی نه هم آن دیگرست سالک تن، سالک جان، دیگرست باز جان و تن ز نقصان و کمالهست دایم در ترقی و زوال لاجرم بس ره که پیش آمد پدید هر یکی بر حد خویش آمد پدیدکی تواند شد درین راه خلیل عنکبوت مبتلا هم سیر پیلسیر هر کس تا کمال وی بود قرب هر کس حسب حال وی بودلاجرم چون مختلف افتاد سیر هم روش هرگز نیفتد هیچ طیرHere every pilgrim takes a different way, And different spirits different rules obey Each soul and body has its level hereAnd climbs or falls within its proper sphere There are so many roads, and each is fit For that one pilgrim who must follow it.How could a spider or a tiny ant,Tread the same path as some huge elephant? Each pilgrim’s progress is commensurate With his specific qualities and stateOur pathways differ, no bird ever knows The secret route by which another goes(Attar et. al, 1984, p. 252)

Later, in this part of the book, Attar explains that when a wayfarer becomes aware of their unique quality they become illuminated and aware of all their atoms and the terrestrial furnace of living becomes a celestial heaven for them.

The valley of detachment

After intuitively coming to know their unique qualities, Attar suggests that the wayfarer recognises the insignificance of man in the cosmos. This is a state where one feels detached from the extraneous, and the individual is able to put aside distractions that might impede them from progressing into deeper discovery. This concept in an illuminationist journey has no equivalent in Moustakas’ defined concepts; it can, however, be linked to his incubation phase of heuristic inquiry (Moustakas, 1990). In Attar’s narrative, numerous birds find themselves hindered by their adherence to personal ideologies, material possessions, and attachment to their homeland, leading them to cease their pursuit along the path to discover Simorgh.

گر بریخت افلاک و انجم لخت لخت در جهان کم گیر برگی از درخت گر ز ماهی در عدم شد تا به ماهپای مور لنگ شد در قعر چاه گر دو عالم شد همه یک بارنیست در زمین ریگی همان انگار نیستگر نماند از دیو وز مردم اثر از سر یک قطره باران در گذرIf all the stars and heavens came to grief, They’d be the shedding of one withered leaf; If all the worlds were swept away to hell,They’d be a crawling ant trapped down a well; If earth and heaven were to pass away,One grain of gravel would have gone astray; If men and friends never seen again,They’d vanish like a tiny splash of rain(Attar et. al, 1984, p. 261)

The valley of unity

For many previous mystic teachers, the valley of unity marked the end of the wayfarer’s journey. In this realm, by indwelling in the state of detachment, the inquirer attains eventual illumination, veils fade, and the hidden, interior sun shines through. Here the self is united with its hidden essence, i.e., the celes- tial state of one’s existence, a state in which the birds indwell for a long time. However, although it appears to be a point of convergence, Attar doesn’t consider that this is the end of the journey. The first signs of illumination emerge in this valley to the birds. Unity is very similar to Moustakas’ concept of ‘indwelling’ (1990, p. 24).

هرک در دریای وحدت گم نشد گر همه آدم بود مردم نشدهر یک از اهل هنر وز اهل عیب آفتابی دارد اندر غیب غیب عاقبت روزی بود کان آفتاببا خودش گیرد، براندازد نقاب هرک او در آفتاب خود رسیدتو یقین میدان که نیک و بد رسید تا تو باشی، نیک و بد اینجا بودچون تو گم گشتی همه سودا بودBe lost in Unity’s inclusive span,Or you are human but not yet a man. Whoever lives, the wicked and the blessed, Contains a hidden sun within his breastIts light must dawn through dogged by long delay; The clouds that veil it must be torn away Whoever reaches to his hidden sunSurpasses good and bad and knows One.This good and bad are here while You are here; Surpass yourself and they will disappear(Attar et. al, 1984, p. 271)

The valley of wonderment

Attar believes that, after unification and the elevation of the state of the self, the wayfarer faces the – or a – crisis of identity. The person is not their previ- ous self, and this is confusing. The person loses their previous sense of a coherent self-identity. In his story, many birds perish in this valley because they cannot recognise who they are anymore. Attar argues that what saves some of the birds in this crisis of identity is the overwhelming, introspective, and contemplative love that is the essence of the illuminationist.

مرد حیران چون رسد این جایگاه در تحیر مانده و گم کرده راه هرچ زد توحید بر جانش رقمجمله گم گردد از و گم نیز هم گر بدو گویند مستی یا نهاینیستی گویی که هستی یا نهای در میانی یا برونی از میان بر کناری یا نهانی یا عیان فانیی یا باقیی یا هر دوییا نهٔ هر دو توی یا نه توی گوید اصلا میندانم چیز من وان ندانم هم ندانم نیز منعاشقم اما ندانم بر کیم نه مسلمانم نه کافر، پس چیملیکن از عشقم ندارم آگهی هم دلی پرعشق دارم هم تهیHe is lost, with indecisive steps you stray the Unity you knew has gone; your soulis scattered and knows nothing of the Whole. If someone asks: ‘what is your present state? is drunkenness or sober, sense your fate,and do you flourish now or fade away? ‘the pilgrim will confess: ‘I cannot say; I have no certain knowledge anymore;I doubt my doubt, doubt itself is unsure; I love, but who is it for whom I sigh?Not Muslim, yet not heathen; who am I? My heart is empty, yet with love is full; my own love is to me incredible.(Attar et. al, 1984, p. 278)

The valley of selflessness

Attar’s final stage exists for those who survive the realm of the valley of identity crisis. Leaving the valley of wonderment, the searcher reaches the state of Fana (انف). This word is difficult to translate. Some writers have interpreted it as anni- hilation or even death, but this interpretation is too literal and fails to reflect the subtle ethos of the word. None of the birds who eventually arrive to the court of Simurgh dies or disappears. Instead, their egos fade away, and their inner excellence illuminates their surroundings to such an extent that their former self (now a realm of shadows) cannot be seen anymore, even though it still exists. I would suggest that the ‘annihilation’, therefore, is not death but the emergence of a different state of being, a resolution where the self disappears (self-loss). The searcher is subsumed within beauty, they are no longer what existed, but rather something dissipated but present. This state has been inter- preted across generations in many masterpieces of Iranian-Islamic art and the reason these works are not signed is because the ‘self’ of the creator is under- stood to be absorbed into the excellence of their artwork. In terms of heuristic inquiry, this is similar to Sela-Smith’s (2002) concept of surrender.

صد هزاران سایهٔ جاوید تو گم شده بینی ز یک خورشید توبحرکلی چون بجنبش کرد رای نقشها بر بحر کی ماند بجایهر دو عالم نقش آن دریاست بس هرک گوید نیست این سوداست بسهرک در دریای کل گم بوده شد دایما گم بودهٔ آسوده شدگر پلیدی گم شود در بحر کل در صفات خود فروماند بذل لیک اگر پاکی درین دریا بود او چون بود در میان زیبا بودنبود او و او بود، چون باشد این از خیال عقل بیرون باشد اینWhen sunlight penetrates the atmosphere,A hundred thousand shadows disappear And when the sea arises what can save The patterns on the surface of each wave?Whoever sinks within this sea is blestAll in self-loss obtains eternal restThe heart that would be lost in this wide sea Disperses in profound tranquillity,And if it should emerge again it knows,The secret ways in which the ways in which the world arose. And evil souls sunk in this mighty seaRetain unchanged their base identity;But if a pure soul sinks the waves surround His fading form, in beauty he is drowned He is not, yet he is; what could this mean? It is a state the mind has never seen(Attar et. al, 1984, p. 288)

The journey in reflection

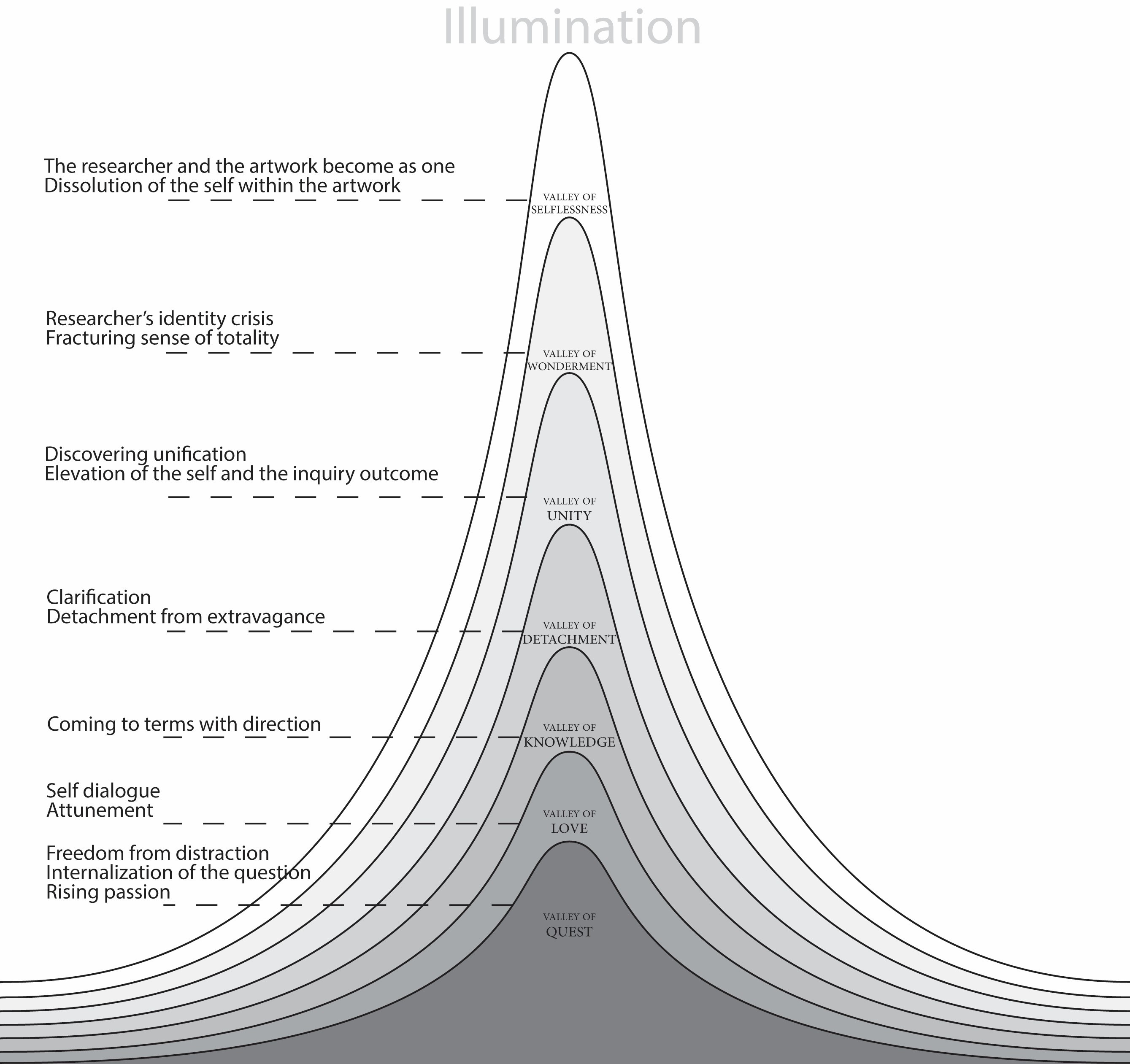

If we summarise the search journey through the valleys (Figure 3.3), we observe a move from a state in which (re)searchers free themselves from distraction and internalise their quest, to one in which they are subsumed within the work (dissipated but present). Unlike certain Western conceptual- isations of a research journey that might end at the fifth stage of realisation resulting from unification (the valley of unity or discussion of findings), Attar’s view of this journey includes two additional phases. The first (the valley of wonderment) may be framed as an identity crisis wherein the (re)searcher experiences a fractured sense of totality. If the (re)searcher progresses beyond this stage, and progresses to the valley of selflessness, they are transformed by the inquiry’s journey and experience a state of ‘oneness’ with their artwork.

FIGURE 3.3 Diagram showing an inquiry as the researcher progresses through the Seven Valleys.

Bridging heuristic inquiry and Persian illuminationism

In this exploration of resonances between heuristic inquiry and Persian Illuminative thinking, we have journeyed through a rich landscape of com- parative analysis. The comparison between Moustakas’ heuristics and Attar’s illuminationist journey of the self reveals remarkable parallels and intersec- tions. In this concluding section, I propose that heuristic inquiry is flexible enough to find functioning resonances in non-Western ways of understanding

research processes. As academia increasingly embraces diverse knowledge systems, this analysis might offer a more holistic and nuanced framework for research practices that operate in interdisciplinary, transcultural, and/or global environments.

Comparing Moustakas’ heuristics inquiry and Attar’s illuminationist journey of the self

Although Moustakas’ heuristic inquiry represents a human scientific search based on seven concepts or processes, his methodology is designed to help a heuristic researcher discover the ‘nature and meaning of experiences’ (1990, p. 9). Thus, heuristic inquiry is a means to an end, rather than a pro- cess that is integral to, and inseparable from its outcomes.

While I accept that Moustakas’ heuristic inquiry is essentially an academic discourse (Oram, 2019) and Attar’s poem is an artwork that metaphorically illustrates the pursuit of self-realisation, I find Attar’s thinking useful in con- structing a framework for my research, and despite certain stylistic differ- ences, the approaches of both thinkers have features in common.

Both acknowledge the importance of tacit knowing (or intuition) that ena- bles subjective and creative connections between the (re)searcher and phe- nomena. Both propose self-dialogue as integral to development, and both emphasise reflection. In both bodies of thought, the (re)searcher chooses to become deeply engaged in the pursuit of knowing and to utilise self- experience in the process. Like Attar’s illuminationist journey of the self, Moustakas’ (1990) heuristic inquiry also encourages the researcher to explore with an open mind and to pursue a path of inquiry that originates inside themselves (Djuraskovic & Arthur, 2010). It is within this internal realm that research discovers its direction and meaning.

However, significant differences lie in Attar’s last two stages and concepts: wonderment and selflessness and Moustakas’ concepts. This may be because these ‘valleys’ emanate from an Eastern gnostic perspective with little equiv- alence in Western thought. Accordingly, these stages and concepts contain ideas that fall outside of Moustakas’ considerations. While Moustakas’ con- cepts raise an awareness of intuitive self-reflection in the realm of the social sciences and artistic research, the valleys of wonderment and selflessness in Attar’s journey are more metaphysical stances.

The valley of wonderment in which the searcher dispels identities is related to the mystic belief that humans are distanced from their divinity. This concept may be described as Fana (selflessness). This is an illuminationist idea that attributes material bodies to the world of shadows. When the self of the searcher is symbolically annihilated, divine light is able to shine within the self and also pass through the (re)searcher. Consequently, the entirety of the (re)searcher turns into an allegorically illuminating being that brightens their surroundings.

Synthesising the thinking of Moustakas and Attar: An illuminationist heuristic methodology

Heuristic inquiry offers a unique method ‘in which the lived experience of the researcher becomes the main focus of the study, and it is used as an instru- ment in the process of understanding a given phenomenon’ (Brisola & Cury, 2016, p. 95). The primacy of intuition doesn’t predicate a rejection of reason- ing in either illuminationism or heuristic inquiry because rational thinking resources knowledge by presence (Ziai, 1990) and explication and creative synthesis (Moustakas, 1990).

According to ‘knowledge by presence’, when the essence of a phenome- non becomes present to the (re)searcher, they will experience it as an imme- diate and unmediated knowledge of themselves. To an illuminationist, to know something, the (re)searcher must elevate themselves through praxis. Therefore, ‘knowing’ is more than simply being informed; it must constitute an active engagement with the object of inquiry.

The knowing being and the known thing are different gradations of allegor- ical light. To be able to know a thing, both the (re)searcher and the object of inquiry have to be uplifted from darkness. The (re)searcher will be illuminated by journeying. Such a journey takes the form of a vigorous, dynamic engage- ment with the context and content of the research in such a way that the self of the (re)searcher becomes increasingly conscious of the self and the subject. In other words, they become illuminated. In Suhrawardi’s (1186/2000) illumi- nationist thinking, the dedicated work of the (re)searcher throughout a jour- ney not only illuminates the self but also excites the object of inquiry to the state of illumination. In this process, the self is internalised into the unmedi- ated, immediate subject of inquiry. Here, there is a partial correlation with heuristic inquiry’s emphasis on the internal self as a subject of inquiry. In heuristic inquiry, self-search, exploration, and discovery enable the researcher to pursue a ‘creative journey that begins inside one’s being and ultimately uncovers its direction and meaning through internal discovery’ (Djuraskovic & Arthur, 2010, p. 1569). However, in heuristic inquiry, the self as the subject of inquiry can be differentiated from Attar’s illuminationism, because the journey is neither predicated on illumination of the darker self nor the self’s eventual symbolic annihilation.

Although the subject of inquiry might have been previously illuminated through the praxis of others, the darker self of the (re)searcher will, up until the journey of the inquiry, have been able to see the illumination. Once the (re) searcher becomes illuminated, the light of the self is able to unite with the light of the subject of the inquiry and the two merge. The knowledge that surfaces out of this unified state is innate, intuitive, immediate knowledge that is recog- nisably present, and the (re)searcher instantaneously comes to the state of knowing it. This knowledge by presence can be so direct that the (re)searcher often needs to pause and look back on their journey to understand it.

Sometimes the (re)searcher is so immersed that this reflective understanding becomes impossible, so an external critic is required to observe the process from an objective standpoint. From an illuminationist perspective, the external critic functions as a mirror that reflects the irradiated light of the (re)searcher back to themselves so they can recognise their own light. Thus, supervisors, critical collaborators, and reviewers may be understood as essentially illumi- nating beings who intensify and catalyse the process of becoming illuminated. They, in effect, ‘climb inside’ the subject of inquiry and cast light into dark corners of the pathway.

Conclusion

This chapter navigates the complex relationship between heuristic inquiry and Persian Illuminative thought, proposing a novel approach to research methodology. It highlights how the philosophical underpinnings of Persian thought, with its focus on inner experiences and intuitive understanding, can embrace and enrich heuristic methodologies. This synthesis of methodologi- cal processes and philosophical introspection proposes a cross-cultural shift in research paradigms, advocating for a more inclusive and reflective approach to knowledge creation. By drawing on the metaphorical journey in Attar’s narratives to illustrate the (re)searcher’s quest, the chapter has argued that the birds’ (and the researchers’) journey, although seemingly external, is also an internal journey of understanding. This integration of diverse epistemological perspectives offers a reimagined approach to research, encouraging a more nuanced, reflective, and comprehensive engagement with academic inquiry.

Notes

1 The letter Q (ق) is a sacred letter in the Quran and by itself it can contain a dense meaning. In some sentences it may mean to ‘reclaim your abstinence’.

2 If simurgh is read in a separated form, i.e., si + murgh, the word means 30 birds.

References

Afshari-Mofrad, M., Ghazinoory, S., Montazer, G. A., & Rashidirad, M. (2016). Groping toward the next stages of technology development and human society: A metaphor from an Iranian poet. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 109, 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.04.029

Aminrazavi, M., & Nasr, S. H. (2013). The Islamic intellectual tradition in Persia. Routledge.

Attar, F. ud-Din. (1984). The conference of the birds (A. Darbandi & D. Davis, Trans.; re-issue edition). Penguin Classics.

Bahonar, M. (2010). پرواز های رازنامه ؛ الطیرها رسالة تاریخی روند [Historical trajectory of treatise on birds] 221 فرهنگی کیهان مجله [Keyhan Farhangi Magazine, 221].

Barrett, E., & Bolt, B. (2007). Practice as research: Approaches to creative arts enquiry.

Beheshti, M. (2015). اشراق شیخ منظر از شناسی معرفت [Epistemology according to Suhrawardi].روش 81 انسانی علوم شناسی [Humanities Methodologies, 81]. http://ensani.ir/fa/article/357171

Beheshti, M. (2016). اشراق حکمت در حقیقت شناخت روش[Methods to understand truth in illumi- nationism]. 84 انسانی علوم شناسی روش [Humanities Methodologies, 84]. http://ensani.ir/fa/article/357190

Berenjkar, R. (2019). انسانی علوم با آشنانیی [Introduction to Islamic philosophies]. و مطالعه سازمان دانشگاهها انسانی علوم کتب تدوین [Institution for Editing Islamic Books for Universities].

Brisola, E. B. V., & Cury, V. E. (2016). Researcher experience as an instrument of inves- tigation of a phenomenon: An example of heuristic research. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 33(1), 95–105.

Bronowski, J. (1965). Science and human values. Perennial Library.

Carroll, K. L. (1997). Researching paradigms in art education. Research Methods and Methodologies for Art Education, 171–192.

Chen, C. (2018). Bright on the grey sea: Utilizing the Xiang system to creatively con- sider the potentials of menglong in film poetry [Doctoral thesis, Auckland University of Technology]. Tuwhera Open Access Theses & Dissertations. https://hdl.handle.net/10292/11737

Chilisa, B., & Kawulich, B. B. (2012). Selecting a research approach: Paradigm, meth- odology and methods. In C. Wagner, B. Kawulich, & M. Garner (Eds.), Doing social research: A global context (pp. 51–61). McGraw Hill.

Corbin, H. (1964). Mundus imaginalis ou l’imaginaire et l’imaginal. Cahiers interna- tionaux de symbolisme.

Craig, P. E. (1978). The heart of the teacher: A heuristic study of the inner world of teaching. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 38(12-A), 7222.

Dabbagh, H. (2009). سهروردی خیال و مولانا عشق [Rumi’s love and Suhrawardi’s dream]. ماه کتاب 23 فلسفه [The Philosophy Book of the Month, 23]. https://ensani.ir/fa/article/208622

Djuraskovic, I., & Arthur, N. (2010). Heuristic inquiry: A personal journey of acculturation and identity reconstruction. The Qualitative Report, 15(6), 1569–1593.

Douglass, B. G., & Moustakas, C. (1985). Heuristic inquiry: The internal search to know. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 25(3), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167885253004

Gray, C. (1996). Inquiry through practice: Developing appropriate research strategies. No Guru, No Method, 1–28.

Hamilton, J. G. (2011). The voices of the exegesis. In L. Justice & K. Friedman (Eds.), Pre-conference proceedings of Practice, Knowledge, Vision: Doctoral Education in Design conference (pp. 340–343). The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/41832/

Haseman, B. (2006). A manifesto for performative research. Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy, 118(1), 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X0611800113

Ings, W. (2011). Managing heuristics as a method of inquiry in autobiographical graphic design theses. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 30(2), 226–241 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-8070.2011.01699.x

Ings, W. (2015). The authored voice: Emerging approaches to exegesis design in crea- tive practice PhDs. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(12), 1277–1290. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2014.974017

Ings, W. (2018). Heuristic inquiry, land and the artistic researcher. In M. Sierra & K. Wise (Eds.), Transformative pedagogies and the environment: Creative agency through contemporary art and design (pp. 55–80). Common Ground Research Networks.

Klein, J. (2010). What is artistic research? Research Catalogue, 1–6. https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/15292/15293

Kleining, G., & Witt, H. (2000). The qualitative heuristic approach: A methodology for discovery in psychology and the social sciences. Rediscovering the method of introspection as an example Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.1.1123

Marcotte, R. (2019). Suhrawardi. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2019). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/suhrawardi/

Mockler, N. (2011). Being me: In search of authenticity. In J. Higgs, A. Titchen, D. Horsfall, & D. Bridges (Eds.), Creative spaces for qualitative researching: Living research (pp. 159–168). Springer.

Moustakas, C. (1990). Heuristic research: Design, methodology, and applications. Sage.

Moustakas, C. (2001). Heuristic research: Design and methodology. In K. J. Schneider,

F. Pierson, & J. F. T. Bugental (Eds.), The handbook of humanistic psychology: Leading edges in theory, research, and practice (2nd ed., pp. 263–274). Sage.

Nasr, S. H. (1964). Three Muslim sages. Caravan Books.

Oram, D. (2019). De-colonizing listening: Toward an equitable approach to speech training for the actor. Voice and Speech Review, 13(3), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/23268263.2019.1627745

Polanyi, M. (1964). Personal knowledge: Towards a post-critical philosophy. Harper & Row.

Polanyi, M. (1966). The tacit dimension. University of Chicago Press. Polanyi, M. (1983). The tacit dimension. Peter Smith.

Pouwhare, R. (2020). NgāPūrākau mōMāui: Mai te patuero, te pakokitanga me te whakapēpēki te kōrero pono, ki te whaihua whaitake, mēngāhonotanga. The Māui narratives: From Bowdlerisation, dislocation and infantilisation, to veracity, relevance and connection [Doctoral thesis, Auckland University of Technology]. Tuwhera Open Access Theses & Dissertations. https://hdl.handle.net/10292/13307

Rahbarnia, Z., & Rouzbahani, R. (2014). Manifestation of Khorrah Light [the Divine Light]Illumination in the Iranian-Islamic architecture from artistic and mystic aspects with an emphasis on the ideas of Sheykh Shahab ad-Din Suhrawardi. Naqshejahan- Basic Studies and New Technologies of Architecture and Planning, 4(1), 65–74.

Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications, and theory. Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, C. R. (1969). Freedom to learn: A view of what education might become. C. E. Merrill.

Scrivener, S. (2000). Reflection in and on action and practice in creative-production doctoral projects in art and design. Working Papers in Art and Design 1. https://www.herts.ac.uk/ data/assets/pdf_file/0014/12281/WPIAAD_vol1_scrivener.pdf

Sela-Smith, S. (2002). Heuristic research: A review and critique of Moustakas’s method. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 42(3), 53–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/00267802042003004

Shafi, F., & Bolkhari, H. (2012). سهروردی اشراق حکمت در هنری تخیل [Creativity in Suhrawardi’s illuminationism]. تهران مدرس تربیت دانشگاه [Tarbiat Modares University]. https://www.sid. ir/fa/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=194243

al-Din Suhrawardi, S. (1186/2000). The philosophy of illumination (J. Walbridge & H. Ziai, Trans.). Brigham Young University.

Wagner, C., Kawulich, B., & Garner, M. (2012). Doing social research: A global context. McGraw-Hill.

Walbridge, J. (2001). The wisdom of the mystic East: Suhrawardi and platonic orientalism. SUNY Press.

Walbridge, J. (2011). The devotional and occult works of Suhrawardı ̄the illuminationist. Ishraq̄: Islamic Philosophy Yearbook, 2, 80–97.

Yazdi, M. H. I. (1992). The principles of epistemology in Islamic philosophy: Knowledge by presence. SUNY Press.

Ziai, H. (1990). Beyond philosophy: Suhrawardı’s illuminationist path to wisdom. Myth and Philosophy, 215–243.

Zwanzig, R. (2009). Why must God show himself in disguise? An exploration of Sufism within Farid Attar’s The Conference of the Birds. Disguise, Deception, Trompe-l’oeil: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 99, 273.