Displacement of Self-Continuity: A Heuristic Inquiry into Identity Transition in an Animated Narrative Short Film

This is an article published at SIGGRAPH Asia 2019 Doctoral Consortium: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3366344.3366443

Written by: Hossein Najafi

Abstract

This research considers how a fictional allegory can be employed to examine issues of acculturation, displacement and identity transition [Addis and Tippett 2008]. Using the story of a refugee family, my PhD research by artistic practice explores the implications of reconstructing an identity inside the body of a new culture. The animated short film, Stella, being developed as the final artefact, is designed to serve as a provocative vehicle for considering the social implications of identity loss and transition. Methodologically, the project employs a heuristic inquiry to increase the chances of discovery in a process that is intuitively negotiated [Ings 2011]. In processing the inquiry, I shape the work and I am shaped by unexpected discoveries. Inside this dynamic, I generate a narrative embodiment of theory. This relationship may result in elevating both the self (the writer/director/animator) and the body of knowledge, though the making process [Moustakas 1990]. Beyond its contribution to understanding processes and implications of acculturation, displacement, and identity transition, the project technological significance lies in its propensity to extend the application and demonstrate the potential of deep learning algorithms, performance capture using motion capture technology, and utilising 3d laser scanning and photogrammetry in digital human development.

Research Questions

- What is the potential of animated allegory as a device for unpacking and reflecting upon identity changes in individuals transitioning through states of displacement and integration?

- What is the potential of the visual metaphor of painting to creatively convey and extend meaning in a short film narrative?

In writing, designing, directing and animating the short film Stella, the research employs a heuristic inquiry to activate high levels of creative discovery in what is paradigmatically an artistic, practice-led research project.

Synopsis

Stella and her mother are refugees from a war. Having escaped, they take shelter in a strange, empty sealed room. Exhausted and puzzled they observe running colour stains on its walls. Eventually they realise that by painting themselves with the pigment they can transition forward through rooms in the pursuit of an incrementally better life. Stella is more adaptable to the new conditions and colours, but her mother has difficulty painting herself brightly and thereby divesting herself of previously held cultural values. As they progress through increasingly better but more demanding rooms, their relationship deteriorates to the point that the mother refuses to paint herself anymore and turns back, wanting to regain what she sees as her diminishing identity. However, in forsaking the painting process in bright colours she gets lost as she transitions back through rooms she has previously entered. She finds herself unable to remember facets of her identity. Conversely, Stella adapts quickly to increasingly changing conditions and finally enters a new world that appears beautiful but entirely painted. Although she achieves a pleasant life here, it is fraught with bitter memories of losing her mother. She marries another refugee in this new world, but her child is born with a disability and she loses her ephemeral contentment. Finally, she decides to find her way back home where she hopes to reconnect with her mother. On her way back home, she gradually loses colour and becomes real. In this process she sees that her child’s disability also begins to disappear. When she eventually returns to the war zone, the battle is over, and she locates her mother who has happily regained her identity.

Significance

Given the ongoing issue of refugees’ experience, the use of an animated narrative may afford a broader access to the experience and issues such people face as they navigate liminal states. By writing, designing and directing this narrative, I seek to provoke thinking surrounding identity and the “multiple layers of consciousness, connecting the personal to the cultural” [Ellis and Bochner 2000]. In such work the artistic practitioner may enable audiences to engage intellectually, emotionally, aesthetically [Figure 1] and morally with a narrative [Ellis and Bochner 2000].

Figure 1. a visualisation of Stella emerging out of the white walled liminal world with her newly forming identity, generated using deep learning (based on Gatys et. al, 2015). Hossein Najafi (August 2019)

In this heuristic research, the technological potentials will be explored through narrative and metaphor. Building upon earlier work that sought to apply a painterly aesthetic inside live action footage (Orinoco Flow, Geoghegan, 1988); (What Dreams May Come, Ward, 1998); (Somebody that I Used to Know, Pincus, 2010); (Dust My Shoulder Off, Leo, 2016) and (Loving Vincent, Kobiela & Welchman, 2017), I will apply and extend recent achievements in neural network algorithms [Gatys et al., 2015] to develop a method for creating stylistic painting effects on moving objects. This research will offer an alternative to current frame-by-frame work like Loving Vincent, (Kobiela & Welchman, 2017) or physical painting of the characters and props as in Dust My Shoulder Off (Outerspace Leo, 2016).

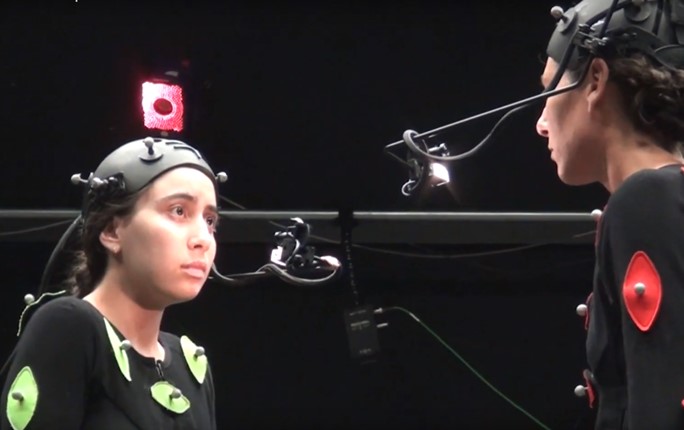

Figure 2. utilising motion capture technology in performance capture, recorded at AUT Motion Capture Lab. Hossein Najafi (August 2019)

Given the democratisation of visualising technologies [Feenberg 1999, Friedman 1999, Jesiek 2003], the thesis provides an example of how a complex film can be made without the assistance of production companies, investors and expensive postproduction studios by utilising motion capture technology [Figure 2], 3d laser scanning [Figure 3], photogrammetry and computer-generated imagery.

Figure 3. using 3d laser scanner to digitise actors. AUT BioDesign lab. Hossein Najafi [August 2019]

Self, Identity and Autobiographical Memory

Historically the soul was a dominant explanation for the nature of humanity [Campbell 2000, Campbell 1949], but this was eventually replaced by notions of self as a purposeful long-lasting kernel of the person. The self has been extensively studied both objectively, (the instant present self – as an immediately perceived I) [Prebble et al. 2013] as well as subjectively, (the phenomenological self - as me). In this second mode, the self is temporally extended and enables the individual to time-travel to the past and live with previous experience in the form of memory and nostalgia [Prebble et al, 2013].

The self is multifaceted [Markus and Nurius 1986] and includes personal identity and social identity. Nelson [2000] suggests that, through exposure to other people and objects, children gradually develop an ‘en-cultured self’. This self helps the person define and differentiate between themselves and their surroundings. She suggests that from the en-cultured self, ‘personal identity’ develops gradually through the individual being exposed to ideological and religious agendas or through realisations of distinguishing features like race or wealth. As humans develop a sense of identity, they are expected to become members of certain groups, (for example a nationality or religious community). Moffet [2013] observes that humans are highly adaptive to new groups and are the only vertebrate that live in groups of more than 200 members. He also suggests that we are ‘wired’ to accept anonymous groups. In other words, consenting to stranger groups is an evolutionary feature of our species. Sani, Bowe and Herrera [2008] suggest that identity structures made by an en-cultured self within group membership, has distinguishing features that enable other human beings to sense continuity in a collective way. They suggest that individuals feel the groups to which they belong are persistent and this unifies them and provides people with higher levels of social well-being. Tajfel et al. [1979] have argued that membership to social groups determine an important part of identity in both major theories of identity: social identity theory and self-categorization theory [Turner and Oakes 1986]. So psychological perceptions and internal experiences of a person are largely influenced by features of the group to which they are linked [Ellemers and Barreto 2001].

The network of identities that people try to link to, plays a critical role in identity transition. Iyer et al. [2010] suggest that individuals build up new identities by reformatting their previous network of social identities and they transit to a revised updated identity by a constant reference to this network. This process may have positive or negative consequences for them based on how this reformatting and referencing occurs. Breakwell [2015] notes that sometimes people are unwillingly forced into developing new identities and this can produce significant negative mental conditions. Knippenberg et al. [2002] suggest that this is especially likely when the transition phase requires relatively high levels of change because individuals have to deal with uncertainty and feelings of disconnection particularly when it is not by choice. These changes require them to redirect their identities and re-categorise themselves to be accepted by new identity groups. People adopt different strategies to overcome negative effects of insecurity. Some attempt to posture a distinguishing feature like masculinity or maturity to alleviate the difficult nature of transition [Holmbeck and Wandrei 1993]. Others may use adaptation strategies to manage distress [Lazarus and Folkman 1986] or may seek social support from others. [Underwood 2000].

We cannot talk about self, en-cultured self and identity without investigating memory. The contribution of autobiographical memory to the continuity of identity is evidential [Addis and Tippett 2008]. The neuro-psychological correlation between identity and autobiographical memory can be studied in two ways. First, by investigating the self in the immediate moment. This is the actual self that we continuously perceive in every second of our life. This is called objective self. However, we can also approach the issue using a broader time scale where we phenomenologically send our ‘selves’ to the past and future and we live experienced and imagined worlds.

We know more about how autobiographical memory works than the actual phenomenon of identity [Rubin 2006]. Like other neurocognitive structures, the autobiographical memory system is not an overall integrated and “propositional cognitive structure of homogenized information” [Rubin 2006].

Contrary to our intuitive perception, the self and to be more specific, autobiographical memory, is not something solid, continuous, rigid and stable; It has a protean and changeable nature. In other words, autobiographical memory has a constructive nature as does the self. People may have very clear memories of the past that may be imagination or to be more accurate, ‘false memories’ [Hyman et al. 1995]. These memories may easily be generated by remembering the childhood stories that have been accommodated as real.

Conceptual self emerges out of interacting with the autobiographical knowledge base and contributing to the organization of its hierarchical units and thematic grouping of life-time periods and general events [Conway et al. 2004]. In amnesia, normally, the conceptual self is preserved even if the associated episodic memories may be missing [Klein et al. 1996]. It appears that the deepest form of memory may remain when brain damage impairs the formation of new episodic memories [O’Conner et al. 1995]. This is why the Self Memory System model is categorized as a separate system that contains mostly non-temporal self-structures. These memory structures help the individual to define the self, others and interact with his/her surroundings [Pasupathi 2001]. The surroundings are formed by exposure to family and social life, education, beliefs, myths, and narrative culture - especially media [Burner 1990].

Methodology

In creating the allegorical narrative Stella, I function as critical insider [Duncan 2008]. This is because as a researcher, I am surrounded with the practice and the context of the inquiry and as such I am central to my exploration [Griffith 2010] and because of this, and the nature of the project as a navigation of the currently ‘unknown’ [Ings 2015], I employ what may broadly be defined as a heuristic methodology [Douglass and Moustakas 1985, Ings 2011 and Sela-Smith 2002]. The protean nature of creative enquiry demands an adaptive strategy because not only the process but also the questions and problems that arise need to be reflectively adjusted [Ings 2011]. Therefore, heuristic research is considered as a preferred methodology. Accordingly, the direction of the enquiry may change or be adjusted, and new questions may arise [Moustakas 1990, Ings 2011]. Moustakas [1990], suggests that because heuristic research is concerned with interrelated and integrated elements, it restores the “derived knowledge” as a form of creative discovery that accompanies intuition and tacit knowledge. The research starts within the practitioner in dialogue with him/herself. Moustakas [1990] notes that such research “is illuminated through careful descriptions, illustrations, metaphors, poetry, dialogue, and other creative renderings rather than by measurements, ratings, or scores”.

Conclusion

The animated short film Stella [Figure 4] considers issues related to identity transition and liminality. The inquiry asks what happens if a constantly changing environment cuts an individual’s thread to the past and proposes another future. Beginning with Nelson’s [2000] idea of the ‘en-cultured self’ that is constructed through a broad range of connections to groups with whom she has traditionally identified [Iyer et al., 2010], we trace Stella and her mother’s journey through a dynamic environment where they are expected to paint themselves again and again so they can progress into increasingly rewarded ‘lives’. Stella’s ‘collective self’ [Sani et al., 2008] becomes incrementally less able to function by simply using values established in previous networks. In this state, we see her navigating Moreland and Levine’s [2002] ‘transition phase’ where she feels lost and disconnected. Her behaviour may be likened to Iyer et al.’s [2010] reformatting of previous networks of social identities where the individual constantly updates a constant referential identification. However, Stella’s mother is not as adaptive, so she is unable to merge with new networks of social identities and values. As a consequence, she fails to verify her position in the new setting and navigates a state that can be likened to Noel et al [1995] ‘limbo’. Branscombe et al., [1999] discuss her resulting feelings of distress and insecurity. The situation is exacerbated because the woman has already begun reformatting her ‘self’ to survive (and cope] with requirements of the new world challenges. Haslam et al., [2002] would frame her situation as an individual who has loosened her references with her previous network of identification groups and beliefs but is unable to fully merge into a new network, and thus activate a collective continuity that facilitates purposefulness. This situation results in her sense of instability. In Stella’s transitional limbo I employ the metaphor of running paint as a symbolic portrayal of the flow of identity displacement. The concept of the incrementally rewarding or punishing multi-room labyrinth operates as a symbol of the new, complex conditions of liminal states. Drawing on Fearon’s [1999] theories we encounter in these spaces a dynamic interaction between the rooms and their dwellers.

Figure 4. work in progress prototype of digitised avatar of Stella character. Hossein Najafi (August 2019)

References

Donna R. Addis and Lynette Tippett. 2008. The Contributions of autobiographical Memory to the Content and Continuity of Identity A Social-Cognitive Neuroscience Approach. Self-continuity: Individual and collective perspectives.

Glynis M. Breakwell. 2015. Coping with threatened identities. Psychology Press.

Nyla Branscombe, Naomi Ellemers, Russel Spears, and Berjtan Doosje. 1999. The context and content of social identity threat. 35-58

Martin Conway, Jefferson Singer, and Angela Tagini. 2004. The self and autobiographical memory: Correspondence and coherence. 22.5: 491-529.

Don Campbell. 2000. The Mozart Effect for Children: Awakening Your Child’s Mind, Health, and Creativity with Music. HarperCollins Publishers, New York, NY

Bruce G. Douglass and Clark Moustakas. 1985. Heuristic inquiry. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 25[3], 39-55.

Margot Duncan. 2008. Autoethnography: Critical appreciation of an emerging art. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3[4], 28-39.

Carolyn Ellis and Art Bochner. 2000. Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity: Researcher as subject. 733

Naomi Ellemers and Manuela Barreto. 2001. The impact of relative group status: Affective, perceptual and behavioral consequences. Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Intergroup processes, 325-343.

James D. Fearon. 1999. What is identity [as we now use the word]. Unpublished manuscript, Stanford University, Stanford, Calif.

Andrew Feenberg. 1999. Questioning Technology. Routledge. 2012

Benjamin M. Friedman. 1999. The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalization. New York: Random House. 40-44

Leon A. Gatys, Alexander S. Ecker, and Mathias Bethge. 2015. A neural algorithm of artistic style. arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.06576.

Alexander S. Haslam, John C. Turner, Penelope J. Oakes, Kathrine J. Reynolds, and Bertjan Doosje. 2002. From personal pictures in the head to collective tools in the world. How shared stereotypes allow groups to represent and change social reality. 157-185

Grason N. Holmbeck and Mary L. Wandrei. 1993. Individual and relational predictors of adjustment in first-year college students. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 40[1]

Ira E. Hyman, Troy H. Husband, and F. James Billings. 1995. False memories of childhood experiences. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 9[3], 181-197.

Welby Ings. 2011. Managing heuristics as a method of inquiry in autobiographical graphic design theses. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 30[2]

Welby Ings. 2015. The authored voice: Emerging approaches to exegesis design in creative practice PhDs. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47[12], 1277-1290.

Aarti Iyer, Jolanda Jetten, and Dimitrios Tsivrikos. 2010. Torn between Identities Predictors of Adjustment to Identity Change. Self-continuity: Individual and collective perspectives, 187.

Brent Jesiek. 2003. Democratizing Software: Open Source, the Hacker Ethic, and Beyond. First Monday, 8 [10].

Daan van Knippenberg, Barbara van Knippenberg, Laura Monden, and Fleur de Lima. 2002. Organizational identification after a merger: A social identity perspective. British Journal of Social Psychology, 41[2], 233-252.

Stanley B. Klein, Judith Loftus, and John F. Kihlstrom. 1996. Self-knowledge of an amnesic patient: toward a neuropsychology of personality and social psychology. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 125[3], 250.

Richard S Lazarus and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company.1984

Clark Moustakas. 1990. Heuristic research: Design, methodology, and applications. Sage Publications.

Hazel Markus and Paula Nurius. 1986. Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41

Fabio Sani, Mhairi Bowe, and Marina Herrera. 2008. Perceived collective continuity and social well-being: exploring the connections. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38[2], 365-374.

Richard L. Moreland and John M. Levine. 2002. Socialization and trust in work groups. Group processes & intergroup relations, 5[3],

Jeffery G. Noel, Daniel L. Wann and Nyla R. Branscombe. 1995. Peripheral in group membership status and public negativity toward outgroups. Journal of personality and social psychology, 68[1], 127.

Kathrine Nelson. 2000. Narrative, time and the emergence of the encultured self. Culture & Psychology, 6[2], 183-196.

Margaret G. O’Connor, Laird S. Cermak, and Larry J. Seidman. 1995. Social and emotional characteristics of a profoundly amnesic postencephalitic patient.

Sally C. Prebble, Donna R. Addis, and Lynnete J. Tippett. 2013. Autobiographical memory and sense of self. Psychological bulletin, 139[4], 815.

Monisha Pasupathi. 2001. The social construction of the personal past and its implications for adult development. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 651-672.

David C. Rubin. 2006. The basic-systems model of episodic memory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1[4], 277-311.

Sandy Sela-Smith. 2002. Heuristic research: A review and critique of Moustakas’s method. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 42[23], 53–88.

Henri Tajfel, John C. Turner, William G. Austin, and Stephen Worchel. 1979. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. The social psychology of intergroup relations, 33[47], 74.

John C. Turner, Penelope J Oakes. 1986. The significance of the social identity concept for social psychology with reference to individualism, interactionism and social influence. British Journal of Social Psychology, 25[3], 237-252.

Patricia W. Underwood. 2000. Social support. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Joseph Campbell. 1949. The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

Mark W. Moffett. 2013. Human identity and the evolution of societies. Human Nature, 24(3), 219-267.

Jerome S. Bruner. 1990. Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

Morweena Griffiths. 2010. Research and the self. In: Biggs M and Karlsson H (eds) Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts. London: Routledge, 167–185.